Rachel Ha’o

One of the first things a product manager does upon inheriting a product is build a growth model. At its simplest, that’s a spreadsheet that backs up the revenue number they’re responsible for into a list of measurable inputs they can change. If that sounds familiar, it works the same in sales.

Every sales team’s growth model spreadsheet tends to look different because it should reflect the unique dynamics of the business. The more specific to the business, the better. That said, effective ones tend to have:

By far the most common way to build that model is in a spreadsheet, which begins simple, but evolves into greater complexity and accuracy over time.

The model should summarize data that you know to help you peer into the future. It should help you forecast beyond the present quarter and team, and to run simulations to help sales managers answer leadership’s questions like whether they’ll need more headcount to hit their number.

“One helpful part of this analysis is that it helps identify key bottlenecks. If your plan to generate 2x in revenue requires you to have 5x the sales team headcount when it’s been hard to find even one or two good people, you know it’s not realistic. If your SEO-driven lead generation model assumes that Google is going to index your fresh content faster and with higher rank than it’s ever done, then that’s a red flag.”

Andrew Chen, General Partner, Andreesen Horowitz

50% of high-performing sales organizations have well-documented sales processes that are explicitly structured, compared to 28% of underperforming organizations.

Hubspot

One of the biggest errors people make with models is creating a model where the growth rate is inputted, not derived. What we mean by that is if you are inputting a percentage growth rate, that’s just a wish. Because, where is that number coming from? Instead, your equations should end in the growth rate. It should be derived, not inputted.

You’ll know something is off about your growth model if you pull the data into a chart and the growth is just a smooth, straight line. That’s a linear growth rate, and that is now how growth really happens. True-to-reality growth rates flex and weave.

The goal of your compensation (comp) plan is not to lay out a gloriously complex constitution for a new state. It’s to inspire salespeople to sell more. It’s an incentive tool, not a court mandate. As such, the simpler, the friendlier, and the easier to understand it is, the better.

The way you’ll arrive at the compensation plan is by asking how much the sales team needs to produce, and then it’s a negotiation between quota size and headcount. Higher quotas mean fewer reps, but impossibly high targets may mean your managers’ reps don’t get paid—which, as we’ll learn in Chapter 7, is how you arrive at high turnover.

Good comp plans keep reps at the brink of maximum productivity and always trying, and sometimes succeeding, to overachieve.

A good comp plan should be:

Elements of an effective comp plan:

“Everyone’s obsessed with sales capacity. They say, ‘To increase capacity, we’re going to hire more salespeople.’ Because theoretically, you can put $100,000 above everyone’s head and you input that into a Google Sheet and suddenly it looks like you’re at capacity. But the idea that adding people increases revenue is a myth. You need to look at sales capacity alongside sales efficiency. You need to look at win rates, ramp rates, and prospecting efficacy. You should be tracking sales efficiency and using that as a leading indicator that it’s time to grow your team—do it because you’ve got everything right and it’s working, not because it’s not working and you’re hoping more hands will help. They won’t.”

Rachel Ha’o, Global Sales Enablement at Iterable

Truly great capacity growth models also account for how well you’re retaining talent. If there’s an effective SDR to account executive pipeline, and you’re retaining lots of that knowledge as people advance, you’re going to have higher sales efficiency. Whereas if your turnover rate is high, and you tend to hire more outside than inside, you’re going to have lower efficiency, and you’ll need more headcount to hit the same number.

“In smaller companies, when you have a sales leader, who’s managing account executives and SDRs, the SDRs always take a backseat. They’re not directly closing revenue. But they’re the ones who need more of your focus because they’re building the pipeline that’s going to make the revenue closers efficient. Good SDRs source good deals that are easier to close. They also benefit more from better ops and tools because they’re more volume-based, and smaller changes there can have a greater effect.”

Mollie Bodensteiner, Global Revenue Operations Leader at Deel

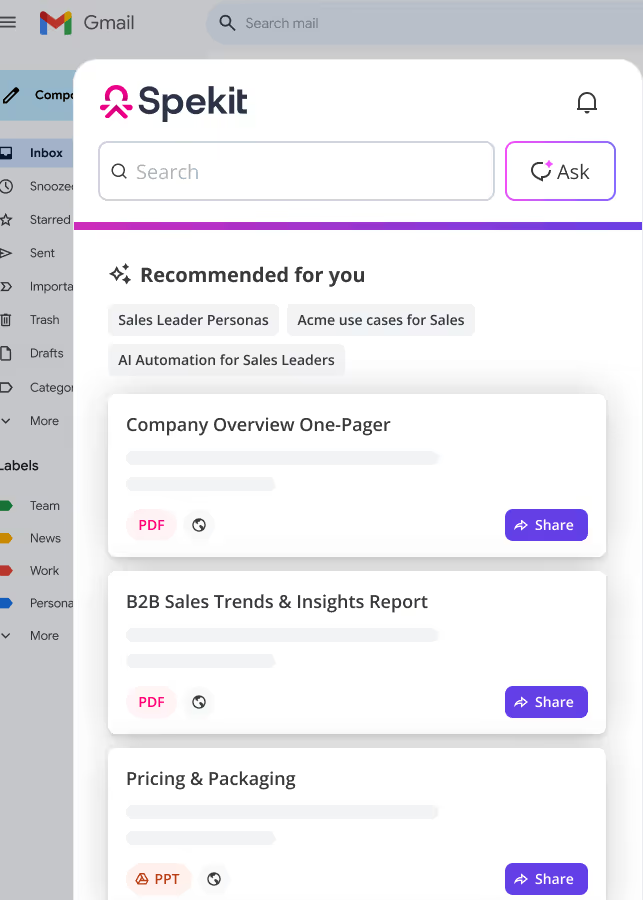

Instantly empower your reps with everything they need to succeed, at their fingertips, the moment they need it.